Despite the cost of living crisis, people continue to live. Fed remains perplexed.

How gig work and the indomitable human spirit are confusing a dire economic machine.

“If we find that consumers or businesses are really starting to feel like that long-term level of inflation … is creeping up, if that’s their expectation, we’ve got to act, and we’ve got to get that under control,” Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic told Bloomberg earlier this month.

Are we doing well? Or are we doing remarkably poorly? What do we make of a world of economic contradiction — in which jobs are plentiful and well-paid, and layoffs and unemployment rampant?

By now, most Americans have become reluctantly aware of the Fed’s charter — at least, as it pertains to them. The Fed raises interest rates to cool inflation, making everything more expensive. Once things are expensive enough, unemployment rises, consumer spending drops, and inflation cools.

In theory.

It’s a dire calculation steeped in human misery, likely conducted by a room full of 80-year-olds and a single COBOL machine. More importantly, it doesn’t seem to be working — enough so that it’s driving dissent even within the Fed.

Unemployment rates are rising —but not enough to kill us all

Unemployment has been rising, just slowly. And that’s what the Fed wants to see — people without jobs. When people don’t have jobs, they don’t spend money. Instead, they just quietly starve, alone in their own (hopefully unheated) homes.

Sorry, rentals. Unheated rentals.

So, unemployment is increasing. That’s the goal. But it’s not increasing as fast as the Fed wanted to see. The ultimate goal of increasing unemployment is to reduce spending — historically, this has worked.

But it’s also possible these two things may have become decoupled in our modern society. At the very least, the complexities of the modern economy may have introduced a confounding level of lag.

So, why do these unemployed consumers continue to spend tons of money on inflated goods?

Why don’t they stop eating or perhaps create a pocket dimension in which to keep their things?

In this world of ever-growing complexity, there are actually a few factors that could be confounding the Fed.

First, although interest rates are much higher, loans are still very accessible. Especially those “Buy Now Pay Later” loans that are now attached to every checkout process. Though the fast money has run out, the easy money is still there — and until the easy money isn’t there, the American consumer may continue to spend.

Some Americans are borrowing from their retirement funds. Others are running up consumer debt. Americans may have:

- become accustomed to a certain lifestyle,

- adopted a nihilistic outlook,

- still some remaining cash reserves to spend,

- or, as the Fed fears, accepted inflation as a new way of life.

It’s also very possible that many of the costs of today’s life are simply inelastic. Grocery inflation has cooled, but prices still remain high. Meanwhile, rent prices continue to rise. Absent crawling into a hole and dying, there aren’t many ways to avoid these things.

The elephant in the room: Where does that money go?

Let’s pause for a moment to also reflect that “inflation” doesn’t mean what it used to. Typically, inflation can occur when people make more money, have more money to spend, and are consequently more willing to spend money for goods and services.

But today, many businesses have also been accused of price gouging. During the pandemic, things became more expensive due to issues of supply and logistics. Now that these have eased, these price targets have remained.

This type of inflation can still be addressed through Fed rate increases. At a certain point, the company has to start adjusting its pricing to stay in business because consumers cannot spend as much.

Assuming that the company does decide to do this rather than continuing a death spiral toward continuous stakeholder-appeasing growth.

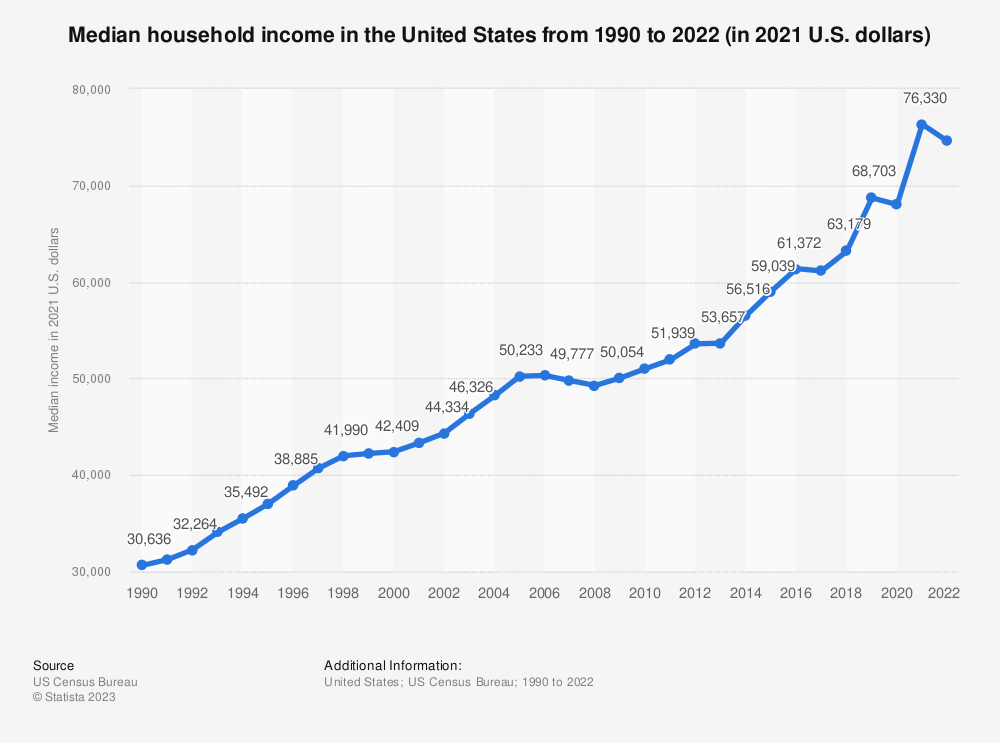

Still, median household income continues to rise

It’s not all the corporations driving inflation. It’s also wages.

In the United States, median household income has been rising. In 2016, the median household income was $63,000. As of 2022, it had risen to $74,000. As real wages rise, consumers have more money to spend.

What do we make of a world in which people are earning more, spending more, and still careening toward economic collapse?

Wages are essentially chasing inflation. Wages aren’t expected to actually reach inflation until 2024. So, when households see wage increases, it brings them to parity with where they were a year ago or even a few months ago.

We’re making more and spending more, but always falling behind.

A world of contradiction — and, well, a whole lot of lies

There’s another layer of obfuscation in our economy: outright lies.

When we read in the news that “jobs are up,” we tend to take it with full confidence. There are numbers, after all, and they all look very official.

But it’s very likely that, for instance, the jobs reports are incorrect — because they simply count job listings.

Likewise, unemployment rates aren’t entirely accurate either. Unemployment rates don’t count:

- those who have given up on finding work,

- those who have freelance employment

- and those who are under-employed.

Perhaps most importantly, most government statistics — and consequently government decision-making — don’t factor in the tremendous rise of gig workers. Consider the most popular gig work jobs (Uber, Lyft, Postmates, and GrubHub), which both increase the cost of goods and services and increase the amount that an individual is earning.

According to PYMNTS, 41% of employed consumers tackle inflation by performing gig work. In other words, they’re simply doing more work to pay for their consumer goods — and, consequently, inflation isn’t as chilling.

So, is the economy good? Bad? A maelstrom of poor, outdated decision-making leading to the end stages of the great capitalist experiment?

Y-ess.

Here are the facts:

- As of 2023, inflation has still significantly outpaced wage growth (Bankrate).

- Unemployment rates have started to sharply increase, with October 2023 at 3.9% (CNBC).

- 2023 has seen nearly 250,000 layoffs in the tech industry alone (Layoffs.FYI).

- In fact, corporate layoffs have increased by nearly 200% (Forbes).

- Monthly job creation is down, with 150,000 jobs posted in October 2023 vs. the 170,000 predicted (CNBC).

Much of the conflict appears to come from a combination of rising inelastic expenses and an increase in elastic earning potential. As expenses such as housing, utilities, and food continue to rise, households don’t cut back — instead, they start to become more creative about how they’re making ends meet.