The lost canonical: How gen AI ushers in the post-truth world

As early as grade school, you learned to cite your sources. If you’re as old as I am, you were told not to use Wikipedia — slightly older still, and you may have engaged in a battle of wills regarding Microsoft Encarta. But the rationale was the same: Know where your information comes from.

A knowledge crisis, bearing down fast

At some point during your life, your aunt or uncle told you something just wrong. They told you that Australia is riddled with drop bears, that you’ll die if you eat Mentos and drink a Coke, that dogs can’t look up, or that capitalism is a viable long-term social structure.

You went throughout your entire life simply passively believing that this was true because there was no reason to question it. And then, one day, someone said “drop bears aren’t real,” “dogs can look up,” or “invest in Bitcoin,” and you realized your entire world was a lie.

We are all a dense archive of things we have heard and read in passing, and the hope is that most of what we consume is correct — and that what is incorrect will someday be corrected.

But with the sudden, uncontrolled introduction of generative AI into our lives and livelihoods, our internal well of knowledge starts to lose coherence.

The world, introduced by GenAI

Of course, we’ve been losing coherence since we started asking ChatGPT for recipes and medical advice. But now, we are currently being inundated by examples of worthless AI snippets. And that matters. Because for many people, searching the internet is how they model the world — how they interact with a broader spectrum of knowledge.

Yes, we know that Google is now telling people to glue their pizza:

And to eat rocks:

But that’s not the most damaging part. The most damaging part is that these generative AI tools are one-offs. They are rendered on demand. They cannot be reproduced.

Our knowledge is diverging.

A long walk off a short bridge

Recently, a new AI snippet has been making the rounds: a user types in “I’m feeling depressed,” and the search engine returns an oblique suggestion: well, jump off a bridge.

This can’t be reproduced, just as none of the others can, and many have questioned whether it’s real.

But that’s just it.

There’s no way of knowing.

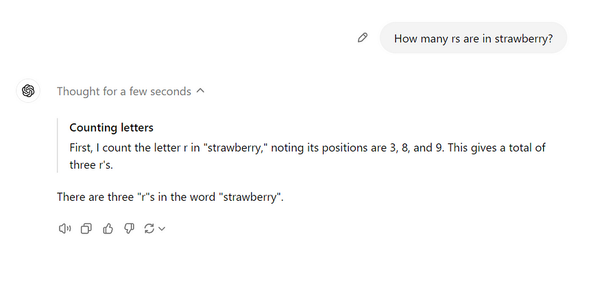

Let’s ask Google a quick question:

OK, that’s pretty timely. But one Inspect Element later and we can simply type this in:

It’s not new that information can be altered and faked. What is new is that no one on the outside can definitively prove this wasn’t a result I received — because there’s no way to reference previous results. There are no canonical results.

There’s only you, me, and our hallucinations.

If an AI generates in the woods…

There are a lot of problems with how we’re currently tackling AI interfaces. We have reached a point at which we are simply throwing large volumes of training data at the problem — all we can do is iterate through more data faster, humanizing our AI rather than creating novel solutions. And, of course, one of the biggest problems with this form of AI is that it can never be more intelligent than the average person.

If GenAI search is able to learn from reports from users effectively, then it could reveal exponential improvement in safety and sanity over its large reporting surface.

But if GenAI search simply relies on user reports alone to guide it, the improvements will be linear — GenAI search will always be a little wrong because people are always a little wrong. Because the average user can’t tell what is real or not real when it comes to physics, history, or the social sciences; they can only tell if a search engine is telling them to eat rocks.

In other words, we can no longer rely on our ability to source information. We are now, once more, in 8th grade, arguing with our teacher about the validity of Wikipedia as a credible citation — but, critically, without any of the traceability or transparency of the Wikipedia platform.